Reading Hotel du Lac

I could be writing about the snow we’ve had in Edmonton, and I’ve taken a lot of photos of the stuff. But there’s always next week for that, and there’s always Instagram.

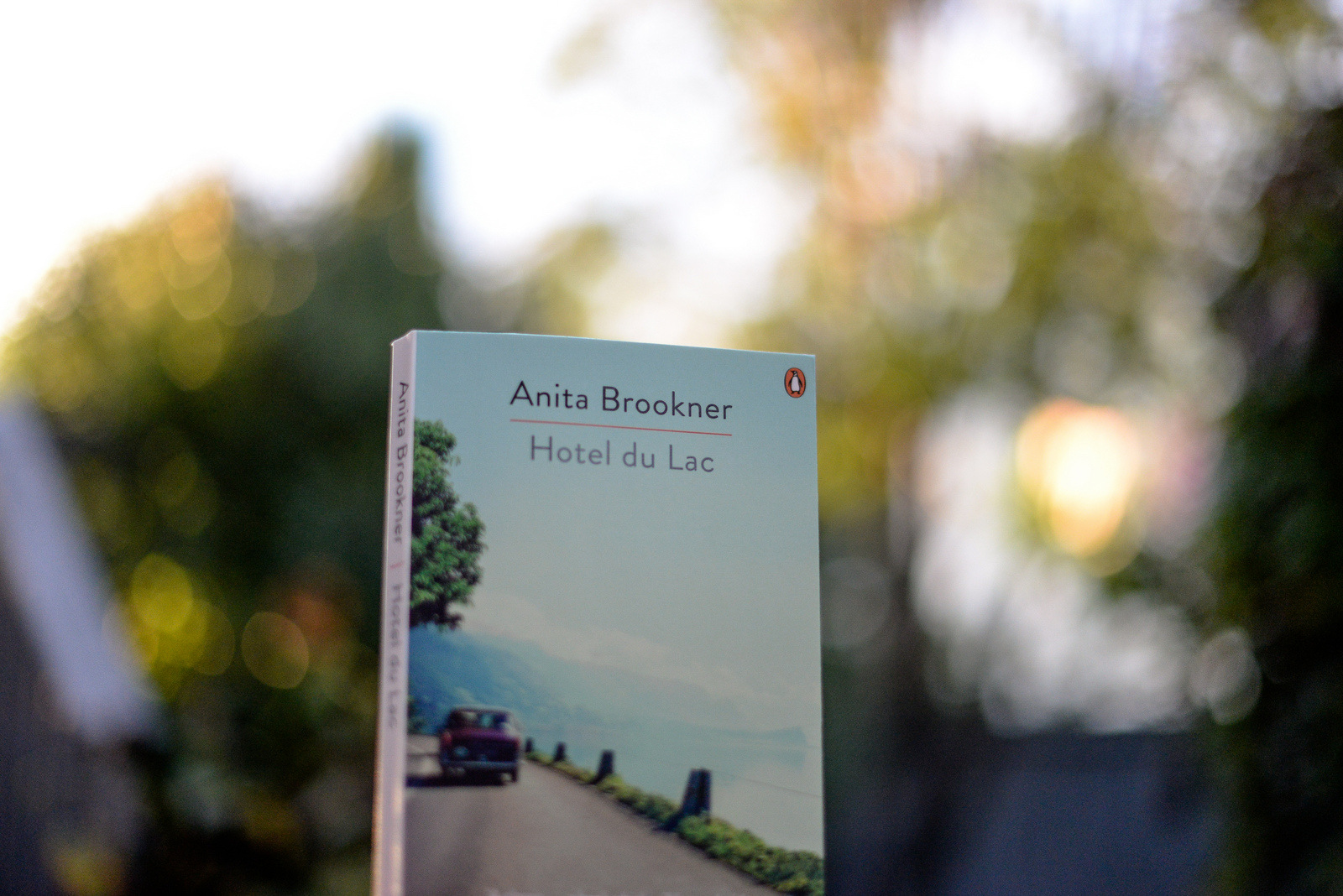

Thankfully, I took some photos of this book I’m so in love with, before it snowed. Many of you will have read it, and maybe read all of Anita Brookner’s 24 novels. This is my first, and I know I’ll be binge-reading many more of them. I feel a bit stupid for not having read her before now, especially since I have a friend with impeccable taste who’s been telling me to do so for years. But who knows what it is that draws one to a book at a certain time.

Brookner has me at the first sentence: “From the window all that could be seen was a receding area of grey.”

This doesn’t seem much, but it sets the tone perfectly, it offers us a vista, which is immediately smudged out. As one enthusiast of her work says in the NY Times: “It should be boring, but it’s invigorating to see the most quotidian things through Brookner’s intelligent eyes.”

Perhaps I am just at the right age to read Brookner. She came late to writing, 53 when she wrote her first book, and I’m 52. Hotel du Lac came out in 1984, which is the year I graduated from high school.

In an interview that appeared in the Telegraph, the book is described thus:

“In Hotel du Lac the timorous, middle-aged romantic novelist Edith Hope, sent into exile by her friends for reneging on her wedding promise to dull, dependable Geoffrey, has her moral probity challenged by the suave voluptuary Philip Neville. 'One can be as pleasant or as ruthless as one wants,' Neville argues. 'If one is prepared to do the one thing one is drilled out of doing from earliest childhood – simply please oneself – there is no reason why one should ever be unhappy again.' 'Or perhaps entirely happy,' Edith replies.”

It’s a wonderful interview, making me wish all the more I’d come to Brookner earlier. For example:

When Brookner was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for Hotel Du Lac in 1984, Liz Calder remembers telephoning her to give her the good news. Brookner replied, 'I think I shall go out and get some shoes re-soled; that will help me keep my feet on the ground.' In fact, she took a rare mis-step. 'I thought of myself much more favourably then,' she says. Thinking she could 'promote a sort of future for myself', she took 10 years off her actual age. A 'friend' – the word is wrung out to drip with sarcasm – ratted on her to The Times. Brookner's response was utterly characteristic; she wrote, complaining of the extreme bad manners in referring to her age and pointing out that 'I am 43, and have been for the past 10 years.' She is still mortified to think of it. 'It was a moment of terrible shame, of course. A silly thing to do.' Craving the good opinion of others is the abiding tyranny. 'You can't avoid it. And everybody compromises themselves in the pursuit of that.'

There is so much in this book to love. But let’s turn to page 127. Edith, the main character, has “been reduced to walking round the garden” while two other characters are talking in the kitchen. One of them observes that Edith is “ In a dream, half the time, making up those stories of hers. I sometimes wonder if she knows what it’s all about.” They laugh, and “Edith, seeing this through the open kitchen door, wondered if she might be allowed in to share the joke. ‘My dear, I’m the one with all the stories,’ she was in time to hear Penelope say. ‘I wonder she doesn’t put me in a book.’” And then this beautiful line: “I have, thought Edith. You did not recognize yourself.”

Which is always the way it is for writers. The persons you have written about never see themselves, and those you’ve not written about will ask, was that me?

Well, I can’t tell you how terribly fond I am of Edith, who has often been told she looks like Virginia Woolf.

From near the end of the novel:

‘Stroll round the deck with me,’ said Mr Neville. ‘You are shivering. That cardigan is not warm enough; I do wish you would get rid of it. Whoever told you that you looked like Virginia Woolf did you a grave disservice, although I suppose you thought it was a compliment. As to vice, there is plenty to be found if you know where to look.’

‘I never seem to find it,’ said Edith.

’That is because you do not give yourself over wholeheartedly to the pursuit. But, if you remember, we are going to change all that.’

’I really don’t see how. If all it involves is giving away my cardigan, I feel I should tell you that I have another one at home. Of course, I could give that away too. But I seem to be too spiritless for radical improvement. I am simply not fascinating. I don’t know why.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘One sees that.’

It’s a happy place to be in, at the first novel of 24 novels, in an author’s oeuvre. I suspect you’ll be hearing more about some of them in blog posts to come.

Lastly, on the shameless self-promotion side of things, I’ve done some sprucing up of my author site, if you’d like to take a look. Likewise, I’ve added a newsletter sign up for Rob’s site, which you can see if you scroll to the bottom of the main page. I imagine he’ll be sending something out about once a month. Thanks for taking a look.