20 (More) Pieces of Advice for Writers

In April of 2019, I wrote a post titled 20 Pieces of Advice for Writers, and I thought, maybe it’s time to look at that again near the end of 2021. I think most of the old advice pretty much holds up. But perhaps there are some new thoughts to add, possibilities to ponder. Because this time we live in calls for some creativity and some re-thinking of how we’ve always done things.

Is all of this advice for you? H*ck no. Please feel free to reject all of this as complete rubbish. Honestly, it’s stuff you probably already know/do. But even if one of the below helps then I’ll have felt useful. Which really, could be the first bit of advice:

21. Try to be useful. Ask how you can be of help. Ask for help.

There is maybe this idea that you have to have read a writer’s book to help them out. But you can still be enthusiastic about it in other ways. (I think everyone knows how to do a shout-out on social media by now). And then, if it’s a book that really speaks to you, maybe think about lavishing just a tiny bit more attention on it. It’s good to just give this purely as a gift with no expectations for the gift to be returned. There’s also no time stamp on this, or on books. You can bestow such gifts years after a book has come out. Books aren’t bread, I always say. They don’t go mouldy.

Conversely, it’s not such a bad thing to ask for help. I wrote a post about Bruce Springsteen saying, “help me out,” and I still think about that moment all the time. I do think people in general want to be of help and so it can be a kindness to ask for help.

I say all this with the knowledge that so many people are just plain exhausted and don’t have a ton to give. It’s completely okay to take a rain cheque. I have a list of books I want to help hype up, but my energy is low right now. I remind myself all the time, books don’t go mouldy.

22. Get a Writing Cardigan, or a Smoking Jacket

Firstly, you don’t need to smoke to wear a smoking jacket. And when I say smoking jacket, I really mean smokin’ hot jacket. To be perfectly honest, I’ve always been the writing cardigan sort. (Possibly a Canadian winter thing). The secret is to always have one that’s good and worn in, but you should probably also start breaking in a new one at some point. You know, the way people will get a puppy when their dog is getting old, as just a sad fact and acknowledgment that nothing lasts forever. But okay, you could also wear a silk jacket in glorious jewel tones, a velvet blazer, a particular hoodie. You might be the type to apply some red lipstick. Or put on your high heels. The point is to put something on to remind you that you’re on the job.

As I said, I’ve always utilized the writing cardigan as my “get into writing mode” signal, but I was reminded of the fact that this was a thing by the recent GQ article by Jason Diamond, titled, “You Need a House Cardigan.” So really, anyone could benefit, not just writers. Also, obviously, my library friends out there will have cardigans for many occasions beyond just house and library.

23. Money is Important

I have written a number of posts where I quote Oscar Wilde saying, “When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss Art. When artists get together for dinner, they discuss Money.” And I do this because it’s hilariously true. I have also quoted the photographer Robert Adams who says, “Money is important. It allows you the power over yourself — your time, your energy, the place you live, the tools you have — to be yourself, to get the job done.”

I don’t really have much to say regarding money other than I hope you have enough, which is obviously not advice. What has worked for me is combining a solid good half-time job with a bit of side-gig cash and the occasional lucky grant. I can’t do anything that is precarious or intermittent because I am married to an artist with a great and brilliant career but a sporadic income. Generally everything works out for us, but we live in a constant state of nervousness because of the unknown and balancing things a bit has been crucial to our vague equilibrium.

I guess the advice part is to figure the money part out first. Because if you don’t, it’s going to wear on your soul something fierce to try and balance everything all the time. I probably took the advice Joseph Campbell gave out a bit too seriously, but it’s worked for me. He talks about how in your day job you might start to do so well that your boss wants to promote you, give you a higher salary, expect more of you. He says, “My advice is: don’t accept the promotion. Don’t accept anything that piles more on you than what you must do to earn your base income…” Which was perhaps easier to enact pre-plague, pre-ridiculous housing and food costs.

24. Have a Daily Project that Grounds You

I suppose this isn’t for everyone, but then, also, I’ve found that a lot of writers do this sort of unofficially anyway. Maybe you write in a diary every day, or take a photo a day, or knit something every day. How about just levelling that up one? You don’t have to turn your project into something, the point is to do it for the purpose of grounding your soul, taking you out of yourself a bit, and to help give your day some shape. There are a few writing practices that I admire that have turned into books. The first is Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights wherein he does, as you would expect, write a short essay each day on things that delight him. I love this book. I’ve blogged previously about Alex Dimitrov’s Twitter project (which is part of his book Love and Other Poems) where he writes about what he loves every day. A recent pleasure has been perusing The Book of Tiny Prayer: Daily Meditation from the Plague Year by Micah Bucey.

25. Take Some Author Photos

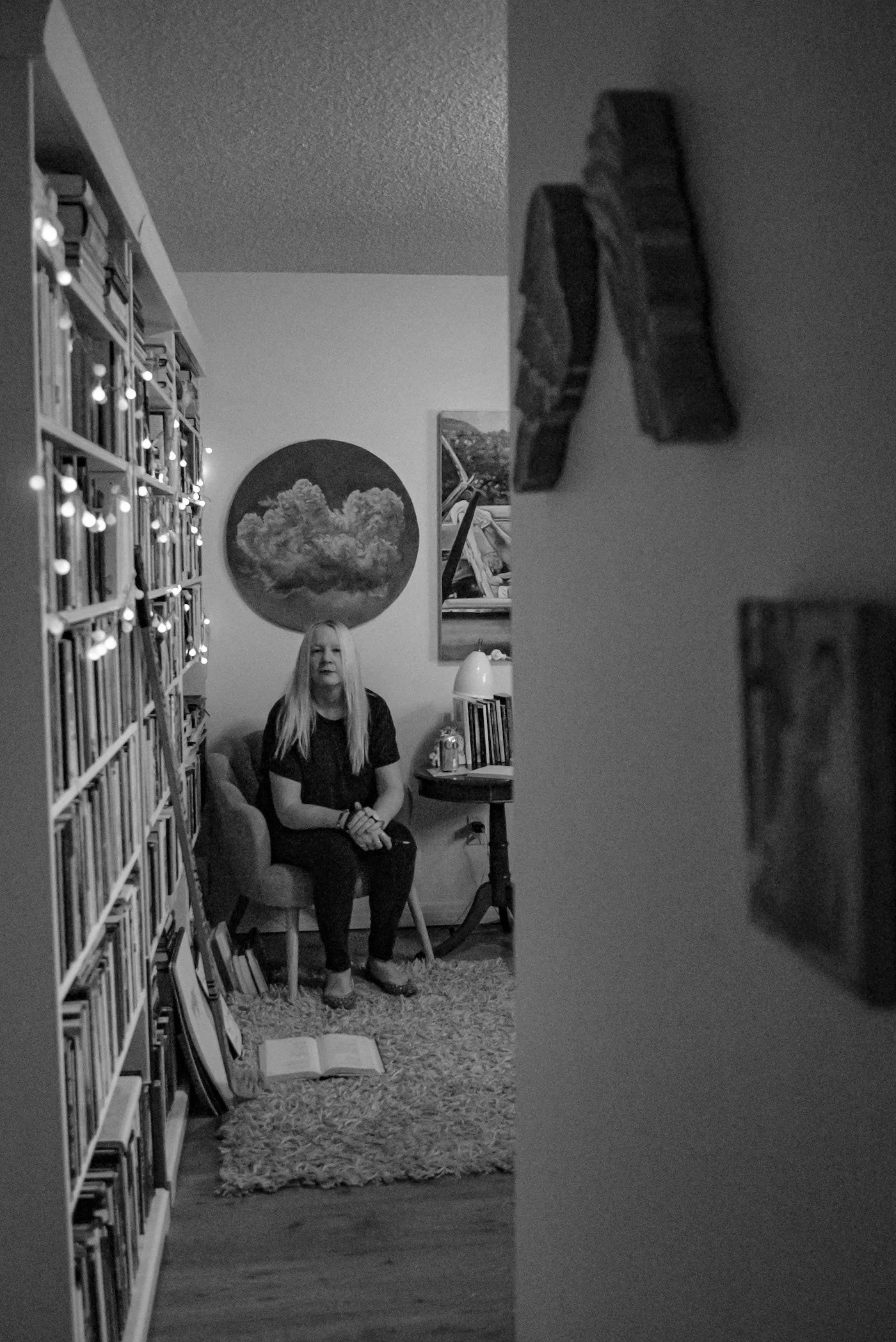

Again, this is just me, but I like taking author photos. I like looking at author photos. I think it’s a beautiful category of portrait photography because authors are not celebrities but they’re kind of often magical, eccentric humans. As a mainly amateur photographer, I love that you can say so much with an author photo. There’s the possibility for depth, eccentricity. A good author photo might tell you something about the should of the writer, and therefore, tell you something about the books they write. I know I have as a goal to do more of this type of photography.

I’ve quoted the poem by Adam Zagajewski “Poets Photographed” before, but here it is again:

Poets photographed

but never when

they truly see,

poets photographed

against a backdrop of books,

but never in darkness,

never in silence,

at night, in uncertainty,

when they hesitate,

when joy, like phosphorus,

clings to matches.

Poets smiling,

well-informed, serene.

Poets photographed

when they're not poets.

If only we knew

what music is.

If only we understood.

I know that often writers think it’s enough to just snap off a phone photo the day that their publisher asks for that jacket cover / publicity photo. Maybe they think it’s too vain to have a photo at the ready. But I think that’s weird especially in the 21st century. My advice is that you ought to consider having a photo taken, a decent set, every year, or twice a year. You don’t need some super professional photographer but you probably need to pay someone a little, someone who will take the time, and look into your soul. Someone who gets what an author photo really is and what for and who for. The thing is, you’ve spent years writing your book. And then you’re just going to slap on a haphazard last minute photo? Hello to the no.

26. Play the Long Game

You know, be in it for the long haul. They don’t call it the writing life for nothing. It’s not just writing, it’s your life. The whole stretch of it.

Likewise, remember (as mentioned above) that your book is not a loaf of bread. It does not get mouldy. In these pandemic times it feels as though all our new shiny books are sinking with hardly a trace. But keep mentioning it and doing all that you can for it. Eventually it will end up in the hands of readers who need it.

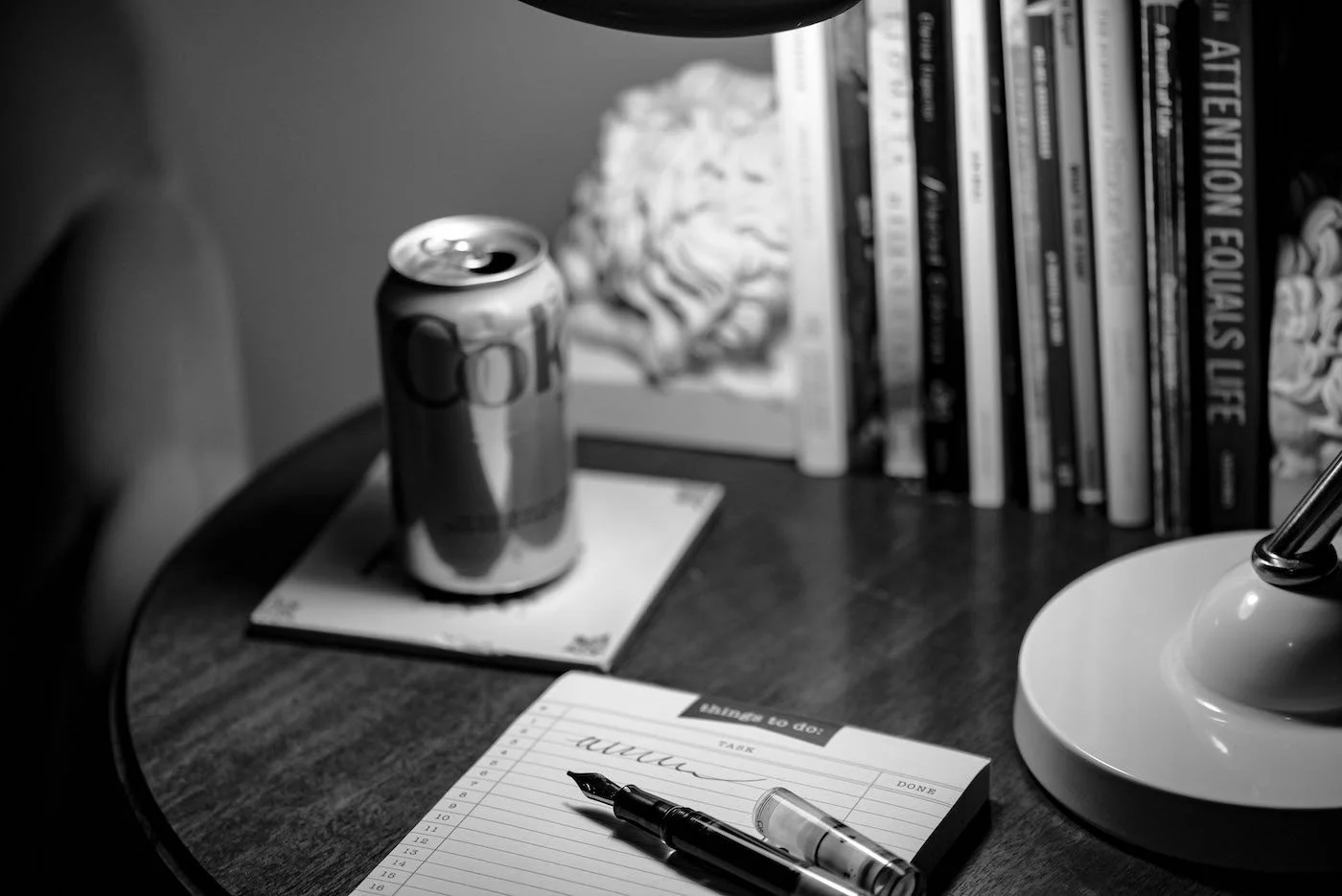

27. Embrace the Secretarial Aspect

I’m stealing this bit from Steven Heighton who in his Work Book says, “The writing life, like life in general, has a sacramental and a secretarial side.” He talks about how over the years, “debts and duties will accrue” and the “clerical mode” will start to “squeeze life from the sacramental, creative side.”

Advice: Find a way to get ahead of that. How? Do the math on your writing. Don’t spend more than you make. Devise a system. Make some spreadsheets. Make schedules, deadlines. Say yes to a lot of things, then say no to a lot of things. Draw giant boxes in your date book and leave them empty for your creative life. Let the secretarial be the great friend of the sacramental.

28. Find Your Audience

I think on social media, anyway, we end up trying to promote our books to other writers, when really this might not entirely be our intended audience. Well, who knows exactly how to find your people. Blogging, though, is one way. (And Kerry Clare has a course coming up in the new year, jsyk). There are lots of reasons to blog but one of the happy outcomes is that you end up connecting with people in ways that you just don’t on social media. It’s quite a delight, I have to tell you.

29. Embrace Contingency

I’ve talked about Stephen Batchelor’s thoughts on contingency a number of times here over the years. They apply to anyone going through uncertain times, but it seems that writers are pretty much continually in this state to one extent or another, and only more so these pandemic days. So from an earlier post:

The thing I’m thinking a lot about lately is contingency. Ages ago I read Living with the Devil by Stephen Batchelor and it has helped me live this life as a writer married to an artist. That existence. We are used to living with flux, uncertainty, albeit not even close to the extent that we are now experiencing globally. But the thought, “if not this, then that” — has helped me a lot. Batchelor talks about contingency: “whatever is contingent depends on something else for its existence. As such, it need not have happened. For had one of those conditions failed to materialize, something else would have occurred. We make 'contingency' plans because life is full of surprises, and no matter how careful our preparations, things often do not turn out as anticipated.”

Embracing contingency “requires a willingness to accept the inexplicable and unpredictable.” We become more fluid and responsive. Batchelor describes the state as being similar to waiting on tables. “Just as a waiter attends to the needs of those at the table [they] serve, so one waits with unknowing astonishment at the quixotic play of life. In subordinating his own want to those of the customer, a waiter abandons any expectation of what he may be next called to do.” The waiter is “constantly alert and ready to respond.” The waiter is invisible yet always there when needed. The waiter is “optimally receptive and alert.” Batchelor also talks about how we hate waiting for things like trains or late friends. We might dip into “resentful frustration.” But he guides: “Instead of regarding it either as an affront to one’s dignity or a waste of time, waiting can be seen as a cipher of nirvana.” The practice of waiting is not passive but is “an alert stillness that cradles perplexity, it is the ground from which we can respond in unpredictable ways to life’s unfolding and the inevitable encounter with others.”

30. Love Things

As with a lot of this “advice for writers,” I think this is probably advice for anyone. Find things to love, be curious about things, be interested in things and in the world and in other human beings. I have no proof, but I think this will make your writing better. I think it makes your writing better because it makes your soul better. And if we are to live a whole life in writing, we need our souls to hang in there, at the very least, and hopefully by more than a thread.

31. Figure Out Where You Feel Good

“Wandering time is positive. Don’t think of new things, don’t think of achievement, don’t think of anything of the kind. Just think, “Where do I feel good? What is giving me joy?””

– Joseph Campbell

32. Don’t Put off Doing Your Work

“We may know that the work we continue to put off doing will be bad. Worse, however, is the work we never do.”

– Fernando Pessoa

Yes, it’s a pandemic. Yes, the world is chaos. Yes, our nervous systems are a holy wreck. Do whatever writing you can do anyway.

33. Not Everyone Will Love You and That’s Cool

Your work is not for everyone. I repeat, your work is not for everyone.

34. Feel Free to say “Jesus, what the fuck?”

There was an interview with the South African writer Antjie Krog that has been taken down from the original source but I wrote about it here. It’s really stuck with me and it ends like this:

What advice would you give to people starting out in a writing career?

I have no advice for younger poets in this technological age – coming from a time where the poem was what mattered, not the poet, her looks, her recipes, her relaxation methods, her self-doubt, his marriages, his Facebook page, agent or public utterances. That is why I didn’t answer some of your questions, those that I thought: jesus, what the fuck?

[Editor’s note: Those questions unanswered included “What do you dislike most about yourself?”, “What are you afraid of?”, “What’s the best piece of advice you’ve been given?” and “How do you relax?”]

Maybe it’s actually fun to be asked about your recipes. I could see places where that might be the right question, or a fun one. But if it’s not, you don’t have to go there, do you?

35. Just Write it Down

Two quotations by Charles Wright:

“What are the determining moments of our lives?

How do we know them?

Are they ends of things or beginnings?

Are we more or less of ourselves once they’ve come and gone?”

– Charles Wright, in Negative Blue

And:

“The unexamined life’s no different from

the examined life –

Unanswerable questions, small talk,

Unprovable theorems, long-abandoned arguments –

You’ve got to write it all down,

Landscape or waterscape, light-length on evergreen, dark sidebar

of evening,

you’ve got to write it down.”

– Charles Wright

In other words, just get to work hey? Stop over-thinking. Which might be coming at the same thing as in #32, but can we ever hear this enough? and from every angle? The work, the work, the work is the thing.

36. Don’t Confide the Essential

From Nicole Brossard’s Intimate Journal:

“You have to be insane to confide the essential to anyone anywhere except in a poem.”

I don’t know if this is true, but you should definitely not do it on Twitter. You know, probably.

37. Say Small Things Intensely

(And also, ignore the critics).

“A critic writes that my poetry fails to see and speak of “the general human condition.” That generality is self-evident. What’s not is the cellular specificity of a fact of a life as it’s lived and laid momentarily to rest in a recongnizable yet somehow strange pattern of words. I’m not interested in being sententious or ruminative. I want to say small things intensely.”

– W.S. di Piero

If you don’t know where to start, start with the small things.

38. Recognize the Value in Silence

This one at first will not sound heartening. C.D. Wright has written a piece called “If one were to try to describe the heed that poetry requires.” (And I honestly think you could replace the word poetry with any art making process). It begins, “Barbara Guest called it orchid attention. She felt the poem should tremble a little.” She talks about the “uncountable hours” a poet will spend in their lives on their tender observations, on their craft. She compares it to scientists spending a lifetime cataloguing and observing one small niche subject. Wright says, “As with most scientific papers, silence may be all that is at the other end. Maybe silence itself has value beyond being humbling. Maybe the record being made is its primary worth, and the rest of our temporal span is meant just for living and for the attention it commands.”

The truth is that even if you receive some attention for your books, the great majority of writers live mainly in obscurity. We live with a lot of silence on the other end. We do our work knowing that it may very well be met with silence. So it’s good to figure out what the value of silence is for you. Yes, it’s humbling. But it’s more than that. And the deeper you go into it, the greater the value.

39. Summon a Fierceness

Again with C.D. Wright, because wow she was so wise. What are we writing for if not to be “trueing” (one of her words) what we see, trueing the world. She says that “poets will have to summon a fierceness equal to the current environment. We will have to meet irrational force with savage insight.” She acknowledges that mostly we will fail. But. “But in so failing and fumbling poets refuse to be accomplices.”

Maybe this will be one of the great questions for the year ahead. How will you summon a fierceness?

40. Blow All the Advice Off and Be a Hermit and Write

I recently read the book Digital Minimalism. There’s a good summing up of it here. And while in the old times, maybe being a hermit meant heading to a cabin in the woods, I think today it mostly means guarding your mental energy and staying away from the fray of social media.

Maybe in the new year it will be time for a reset. (The book advocates staying off the optional technologies in your life for 30 days to do a purge/reset and then after that reintroducing them with intention).

Joseph Campbell talked about going off into whatever hermit-like place of your choosing with your gift. Coming back though, can be tricky:

“Bringing back the gift to integrate it into a rational life is very difficult. It is even more difficult than going back down into the underworld. What you have to bring back is something the world lacks — which is why you went to get it — and lacking it, the world does not know that it needs it.”

When you come back, you have a message to deliver, in the form of the work/writing you have done. It takes a lot of courage to come back after your retreat, says Campbell. There is a time to retreat, and a time to come back. And when you do, you have to find a way to make your return one that is not agony for yourself. There are “modes of having this realization, and the final thing is knowing, loving, and serving life in a way in which you are eternally at rest. That point of rest has got to be in all of it. Even though you are active out there in the world, within you there’s a point of complete composure and rest. When that’s not there then you are in agony.”

While Campbell wrote the above pre-social media, I think the importance of cultivating the state of composure and feeling at rest somehow (in a pandemic!) is at an all-time high. We all know that the idea of the artist needing to be a tortured soul, living in poverty and obscurity is a rubbish one. We are generally going to be making better art if we can feed ourselves, have a decent workspace, and some mental equilibrium.

Maybe in 2022 all we writers should plan a 30 day digital retreat. It’s not the weirdest idea I’ve ever had.

So, as I said, take any of this advice that might work for you and bin the rest. If you have any advice to share please do so in the comments! Would love to hear what is working for you these days.

December 15, 2021