Living with Art

I wrote a book of essays titled, Calm Things and though it was published in 2008, eight years ago, the essays were written starting in 2003. I was in graduate studies and a course in prose writing was offered, taught by a favourite professor from my undergrad, Greg Hollingshead. I wrote "Still, Dead, Silent" for that class and I remember him saying, this is good material, very good material. Which was exactly what I needed to hear.

When I was in grad school, our daughter Chloe (who is now at an art college), was in kindergarten. I have since turned 50. Rob and I have been married for 23 years. Chloe is 18 and her dog, Ace, is nearly 10. I guess I'm listing these numbers because a lot has happened since I wrote Calm Things, but also nothing much has changed.

The book is about living with still life, living with art, with an artist, having a small daughter, and about how precarious it all is always. It's a short book, because I have a love for short books and because it was the kind of book I wished to read. At the time I was steeped in Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek and loved May Sarton's Journal of a Solitude and Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

The essay that I continue to think the most about in my book is titled, "Precarious." It compares the precarious way in which artists live to the composition of a still life - which looks calm and organized but in real life may be stuck together with various adhesives and twist ties. The composition is on the verge of falling apart at all times, and behind the scenes, frequently does.

Since writing the book Rob had a 30th anniversary show at the gallery that discovered his work and that gave him a dozen solo shows through the years. That same gallery closed its doors recently but he shows at three other excellent galleries and his work is in prestigious collections and he's had a room named for him and filled with his work in Calgary's Shaw Court. But believe me when I say that this life of ours is still held together with twist ties.

I've always found the Oscar Wilde quotation to be true:

““When bankers get together for dinner, they discuss Art. When artists get together for dinner, they discuss Money”

”

We often wonder how we've gotten this far, and kind of marvel at the fact that we're still standing. I often tell Rob that he would have been wiser marrying a banker, in fact. There should be a law against a poet and artist marrying, I've often told people.

There's a book we both love by art historian and painter James Elkins, What Painting Is. In it he notes:

"Sooner or later every one of a painter's possessions will get stained. First to go are the studio clothes and the old sneakers that get the full shower of paint every day. Next are the painter's favourite books, the ones that have to be consulted in the studio. Then come the better clothes, one after another as they are worn just once into the studio and end up with the inevitable stain. The last object to be stained is often the living room couch, the one place where it is possible to relax in comfort and forget the studio. When the couch is stained the painter has become a different creature from ordinary people, and there is no turning back."

And through the years we have often said, well, it's not as though we can turn back now. We're in rather too deep.

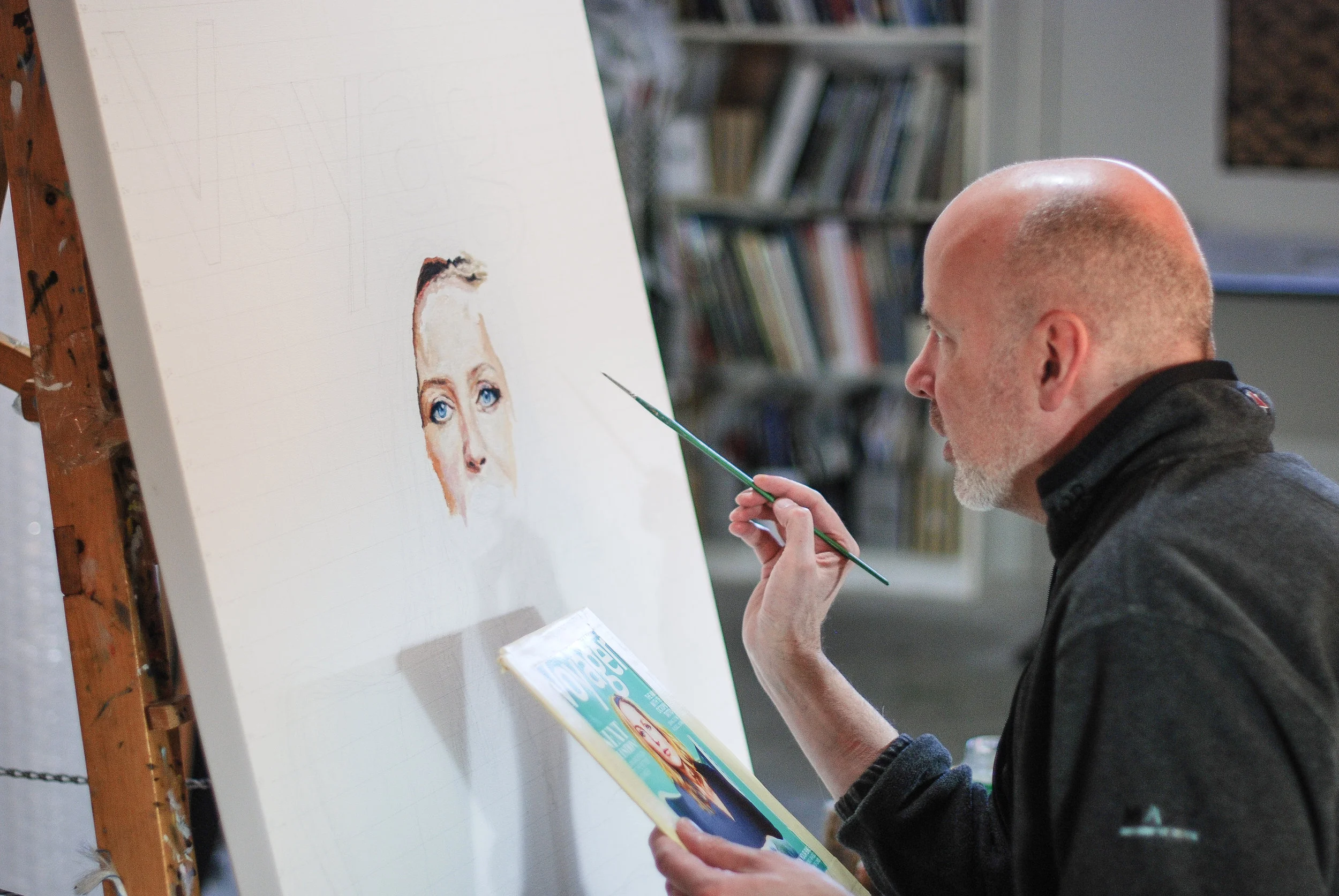

After thirty years of painting primarily still life, Rob decided to challenge himself by painting the figure and also using new methods. Which is, I think, a rather brave thing to do. Most importantly, it's been fun, and this is what motivates him to go down to his quite unglamorous basement studio to paint every morning between 6 and 7am and stay there until 3pm when the dog wants his walk. And then afterwards go back and paint again for a couple more hours on most days. He often talks about taking the weekends entirely off, but rarely does. (There is some math to be done there - 30 years of 10 hour days...)

The Elkins book is one that I frequently turn to because it talks about art without forgetting at all the processes behind a painting. Elkins talks about painting and what goes on in the studio in terms of alchemy, which I continue to find refreshing. So many people who have written about art in poetry or essays have never lifted a brush or hung out in an artist's studio. Elkins says, "It is important never to forget how crazy painting is." And this rings true, too. Our house smells like linseed oil, there's paint on the stair railings, on the couch, and everything revolves around the current work.

“It is important never to forget how crazy painting is.”

I also often borrow Rob's copy of Vanished Splendors: A Memoir by Balthus. I like it because Balthus gets at the holiness of the work, the real meaning of painting. He says,

Working allows me to be present on the first day, in an extreme, solitary adventure laden with all of past history. For this reason I always state that the painter's work cannot be dissociated from his predecessors. Starting from scratch has no meaning if a painter isn't first imbued with the entire history of art, having assimilated it, and starts from there, transfigured by what he is, what he sees and feels.

Before I met Rob he'd been to Europe twice and toured all the great museums. We began our marriage with five weeks in Italy where we visited every museum and church possible. Together we've been to London and Paris and seen the major museums. We've been to Amsterdam and The Hague, Chicago, Washington, and New York City twice, spending almost every moment in the museums. We're completely in accord in this desire to look at art and drink in the history. This has been one of the greatest pleasures of our life.

Which I think also underlines how privileged we have been to be able to do this. But we've done it by giving up quite a lot, too. We've chosen to go on an art tour every couple years rather than go out for dinners, buy fancy clothes, get haircuts, live somewhere cool. Rob works long hours, we stay at home a lot, see few people, live pretty simply. I pretty much attribute having contracted Bell's Palsy a number of years ago to the stress of constantly living precariously. There is a gnawing at the gut those who live the artist life are well acquainted with.

We've thrown ourselves into colour all these years, obviously Rob especially. But I love these words, also from Balthus:

Painting is something both embodied and spiritualized. It's a way of attaining the soul through the body. It can only be attempted by those who know the magnificent jubilation of moving a hand over the canvas, preparing the oils, measuring the canvas's tightness, and throwing oneself into colour.

Most wonderfully for me has been living with this rotating art show, and also with the art that we've kept, paintings we've bought because we loved them and to show support for other artists. And also the paintings that were made for me, my pomegranates, for example. There are a lot of reasons why owning original art is so satisfying, and one of them is that experiencing a work of art at different times of day, in different light, in different moods, deepens one's understanding of art. I think, also, that when you're in the presence of a work painted by someone who lives and breathes art, art history, contemporary art, this is all felt when viewing the art. How enriching this is for the viewer. How full of a quiet joy.

I'll end with more words by Balthus who says,

Our life is marked by trials and tensions, but also by indescribable moments of grace. I always aspired to Bonnard's example of joy, even while experiencing its vanishing and neglect.

He goes on:

Perhaps that's why we're such fervent believers, because of the certainty of light and its revelation that I've often worked for, trying to grasp its dazzlement. That's why painting is a state of grace. No one takes up painting with impunity. One must be worthy of it.

2016