Artemisia Gold – an Essay

Artemisia Gold

I was hungry. I’ll admit that. I wanted to know things. I’d grown up hearing the expression, “your eyes are bigger than your stomach,” and so I knew not to take too much, not to put too much on my plate that would later have to be scraped away, while someone somewhere starved. I hadn’t yet come across the lines by Rumi, “Look at your eyes. They are small, / but they see enormous things.”

I was an extremely visual person but I hadn’t quite realized this and took it for granted. It’s only more recently that I have heard of the apple test, and the terms aphantasic and hyperphantasic. Some people can bring to mind a realistic apple (hyperphantasia), while others cannot imagine one at all (aphantasia). In between, there are those who can imagine an apple at various levels of realism. Some people can bring to mind memories like a movie film and others have visually quieter minds. Seeing and how we see is still so mysterious.

We might like to feel smug because we see things that others don’t or in a way that others can’t fathom. But everyone sees the world uniquely.

All my life I have also been a wildly shy person, so much so that for larger swaths of my younger existence, I spoke little to none in public. This was such an impediment that though I had always wanted to become a published writer, when I learned in my undergraduate university days that this would entail public readings, some in other cities, it occurred to me that I ought not pursue this course. Which sounds quaint to my ears now but it was an abject monumental terror that possessed me then. Any time I had to do a presentation or speak in a class my brain would just white out. Words, pictures, everything was a white blur. I couldn’t envision anything.

What kept me interested in going on was the shard of a belief that there should be space in the universe of writers for someone who wasn’t a public speaking guru or a great beauty or a world traveller.

Writing my first book, I was pulled to learn more about the lives of women artists. How did they get on? How was any of it possible? How to make a life in art? I needed to learn more, and the best way I knew, that I intuited, that I felt (because no one was really guiding me on this), to do this was to imagine. To imagine! Seems almost radical these days. To see things in my mind, to conjure. And partly, one was compelled to do this, because the facts of their lives had not always been preserved.

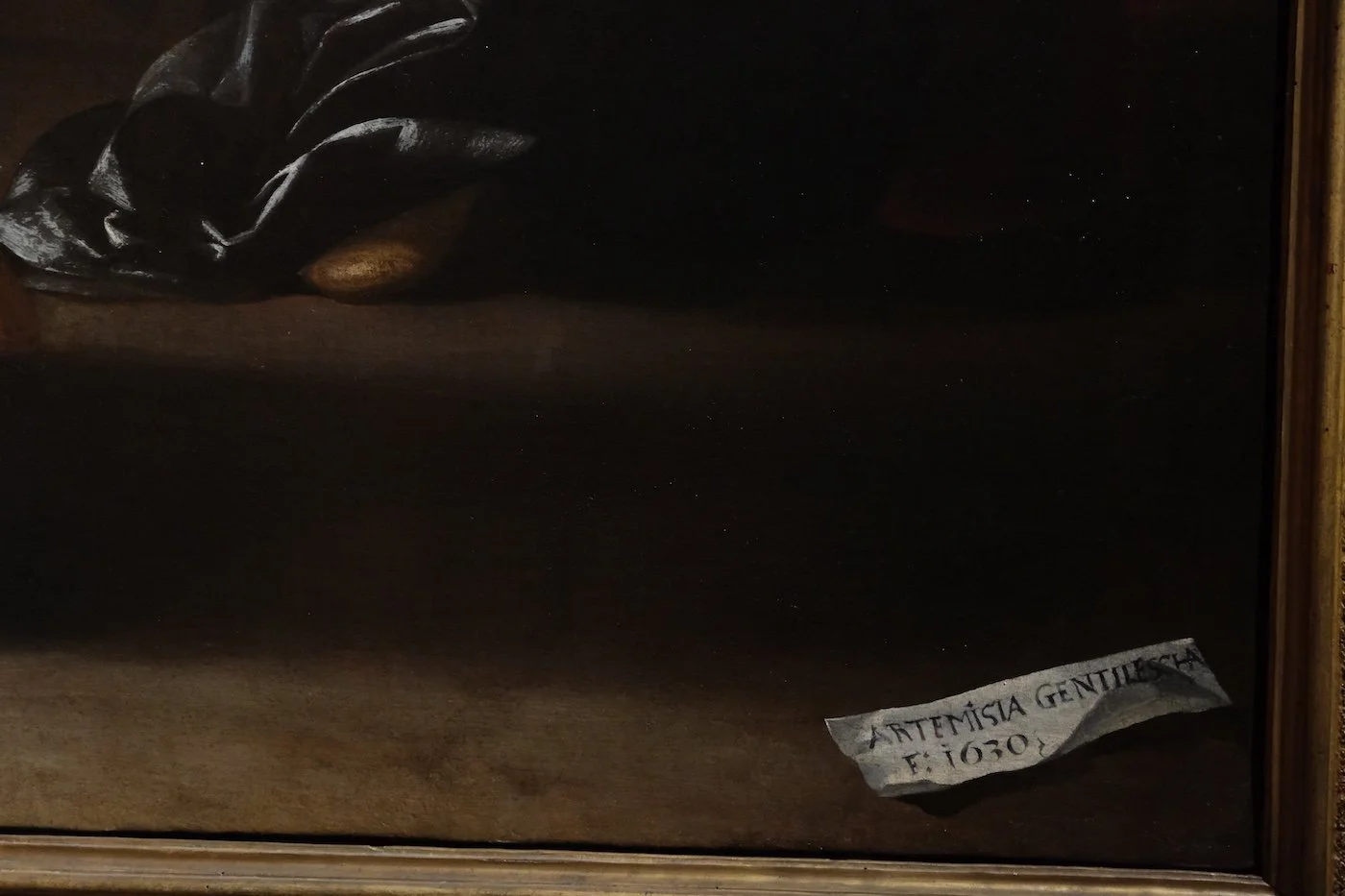

I had finished my English literature degree in 1995 but I wanted more, more!, and so started carting books home from the library, and researching women artists. I’d pore over the pictures in books. My partner, a visual artist, and I had been on a five week honeymoon to Italy and this was the first time I’d seen historical art in person. (This was a time when you found a place to stay at a booth at the train station when you arrived, and when you carried travellers cheques). I remember discovering the work of Artemisia Gentileschi in a book published in 1989 by Mary Garrard and devouring it. I’d initially taken the book from the library and then, when I had to return it, I ordered myself a copy which I still have.

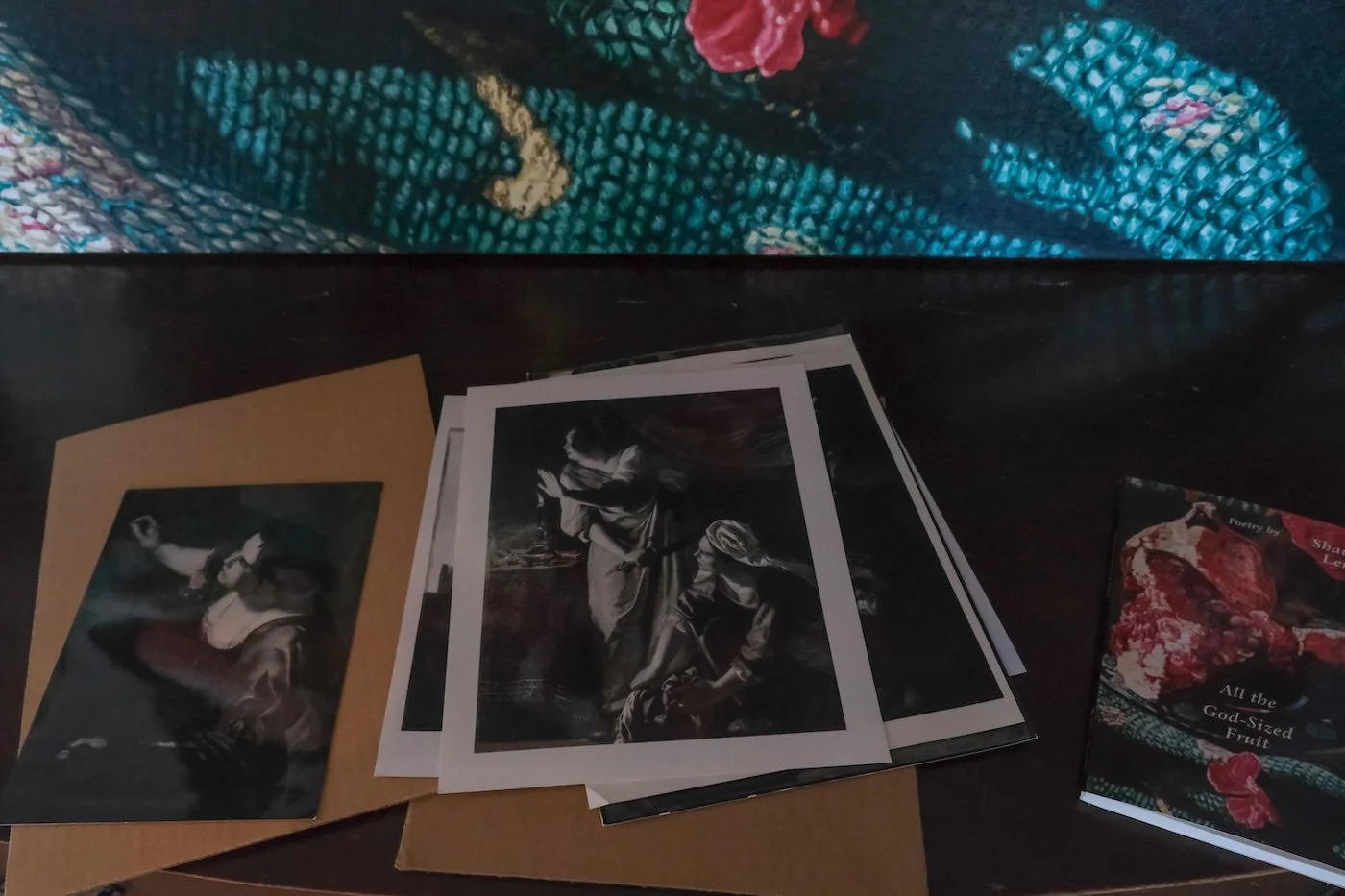

In my book, All the God-Sized Fruit, I wrote about Rosa Bonheur, Rachel Ruysch, and Paula Modersohn-Becker by en-voicing them, which is a subgenre of the poetic form, ekphrasis. The book ended with a suite of poems in the voice of Artemisia Gentileschi. The epigraph to one of the poems was by Virginia Woolf who asked, “Now what food do we feed women as artists upon?” In the poem I had Artemisia bringing to mind, dreaming, a gorgeous and delicious meal. In a poem about her self-portrait as the allegory of painting, I note that she is “straining to see, to know” and that to do so she is “precarious, off-balance” but also she throws her whole body into the act of painting, creating. This image, whenever I come across it in reproduction, still inspires me. Because, you see, this was not heretofore how any allegory of painting had been represented. Instead, the iconology of the time dictated the woman be silenced with a gag.

At the time my book was published there was very little out there about ekphrasis. These days there are workshops, classes, anthologies, etc. but then, the internet was new, and not much existed. When you said “ekphrasis” even among poets, you always had to define it. (I would go on to write a section of poem-essays on ekphrasis in my book Asking).

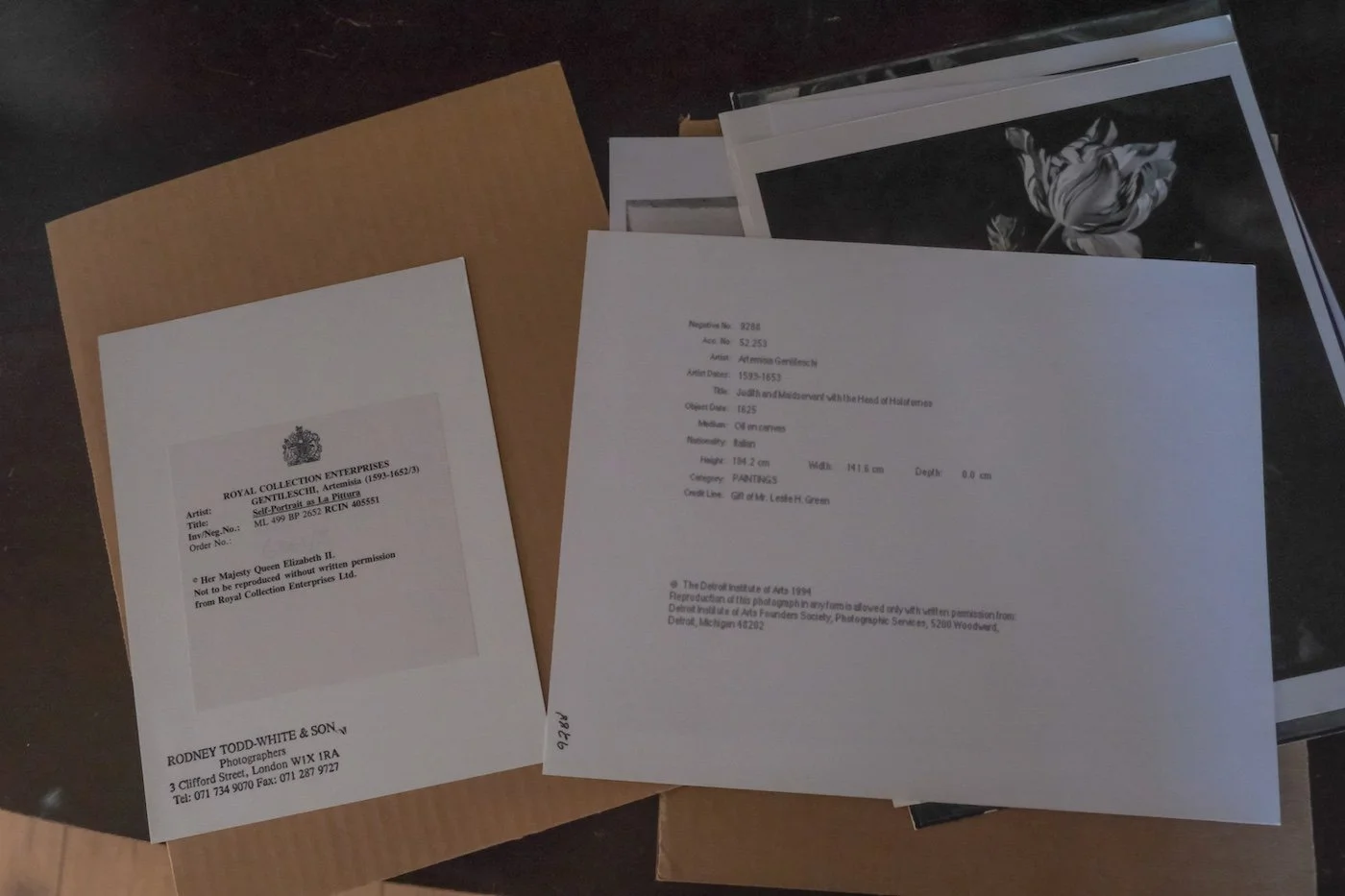

We wrote differently too, in some ways. You didn’t assume the reader knew about the art you were writing about, and they couldn’t just pick up their iPhone and conjure it. So when my editor and I dreamed at first of having images in my book it seemed like just that, a dream. She helped me, she pushed for it, and it was a go, so long as I did the legwork. I wrote emails, and letters, went back and forth. (Nowadays you can ask for permission to use an image from a museum very easily online). I was able to get permission from eleven museums and two of them are for Artemisia paintings. The publisher was sent the photographs and on each one the information from the museum is on the back. We had a small budget, and each museum had a different rate based on the publication run, etc. It doesn’t seem like it would be, but it was a time-consuming process. I still have those very beautiful photo reproductions in my possession.

I had heard at the time that other writers were jealous that I’d managed this feat of getting black and white reproductions in my book. Jealous writers? This seemed to me unlikely.

I’ve seen neither of the two paintings in person that are reproduced in my book. I have though, since the publication of All the God-Sized Fruit managed to see Gentileschi works in New York City at the Met, Rome at the Spada Museum, in Florence at the Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti, and in Naples, most recently at the Museo di Capodimonte and at the Gallerie d’Italia museum.

In Mary Garrard’s book on Gentileschi, the transcript from the rape trial is preserved. Today, academics wonder if the focus on this horrific episode in her life has served to overshadow her work and distort our vision of her. This may be so. I’m still suspicious when someone says we oughtn’t talk about something without also wondering who it would benefit if we were to keep quiet. Viewing the paintings I have over the last several years, I’ve sometimes wondered if those looking at the work know of the history. It seems like they must. There are larger crowds around other works at museums, but in my limited experience the ones that find the Artemisia Gentileschi paintings seem dedicated, looking long, looking closely, reverently even.

When I posted a photo on Instagram recently of the Judith and Holofernes in Napoli, a friend commented that the artist must have met a lot of terrible men! So even if you haven’t pored over the court documents and even if you didn’t know that Artemisia was tortured with a sibille (a device of metal and rope that tightened around her artist’s fingers) during the trial as a sort of lie detector, and her words, “it is true, it is true, it is true,” you can tell that there is some real authentic earned emotion coming through her work. The paintings don’t keep quiet, silent though they are.

Women who have suffered similar abuse have been drawn to the paintings and when the #metoo movement took place, it seemed many were also motivated to reconsider the work of Artemisia Gentileschi in blog posts and articles. As for me, what has captivated me all these many years? While I’ve not experienced this type of trauma, I have always valued and been inspired by the way that she turns the circumstances of her life into virtuosic, powerful, and beautiful art. What she was doing was reenvisioning these women – Lucretia, Cleopatra, Esther, Minerva, Artemis, Persephone, Susanna, Judith etc. – looking at them from another perspective.

Her work has had some recent attention – there was a show in London devoted to her at the National Gallery in 2020-21, but still she’s not a household name. Though perhaps fewer artists are in our time. I mentioned to someone travelling to Amsterdam lately that they were so lucky because they’d get to see some Vermeers, and they had never heard of Vermeer. Fair enough though right, because there is a lot vying for our attention these days.

I think about this sometimes when I consider my own level of fame. There are maybe say, a thousand people who know that I’m a writer. To be generous, maybe two thousand as I sold over that many of my novel Rumi and the Red Handbag several years ago. I think about this as I walk amid the stacks of fiction at the library where I work and though I read quite steadily, there are reams of authors who I’ve never heard of and whose books I will not have a long enough life to peruse. The goal for the average writer or artist in making art is not to become a household name – that is generally unattainable – but to make a life in art. To tend to your own soul while not squandering your gifts, and to express something of your existence while here on earth, is a worthy pursuit.

I won two relatively small but satisfying awards for that first book of poetry, All the God-Sized Fruit, and my second book came out a couple of years later, which maybe seemed like a quick follow-up but the mechanism for publishing that first one had been slow. I wasn’t expecting anything, to be honest I was just happy that McLelland & Stewart had picked it up, and that Tim Lilburn was to be my editor, a poet I esteemed. My first book hadn’t received all that many reviews, but this second one did. There were some good ones. I don’t remember them.

I do remember a publicist from M&S telling me that a sort of mediocre review had been published and I said, “so long as they spelled my name correctly.” Her reply, “well, about that...” My first name was spelled with a U throughout the piece. Two others stuck out for me, and I’ll quote from them, but first, let’s remember the literary landscape circa 2001. There was a book reviews section in most newspapers, and then a removeable section in the Saturday Globe and Mail. The National Post also had a reviews section, but most writers I was acquainted with didn’t subscribe. Your local paper didn’t usually have a syndicated piece but there were fresh reviews. So while the Edmonton Journal was kind, The Calgary Herald didn’t have any compunction about posting whatever the reviewer had sent them. Very hard-nosed of them, I suppose. One can’t fault them especially from this vantage point in our timeline where there are no reviews pages in newspapers to speak of.

This second book, Against Paradise, was originally titled something long and less marketable, but renowned editor and publisher Ellen Seligman suggested the one that stuck. So I’ve always been fond of that title, which was taken from one of the poems. I’m still fond of the cover, and I’m fond of the blurb that Tim Lilburn wrote for the book. I have no regrets. I wrote what I could at the time, a young woman with a small child married to an artist, living in Edmonton, Canada, yearning to know more of the world, to travel, but not finding that to be in her means. Instead, she armchair travels, takes books out of the library, sits and takes notes at odd times, and she writes when her husband takes their daughter to visit all of the old and infirm family members in care homes and hospitals, old folks homes and nunneries.

In the National Post, David Solway reviews the four M&S poetry books that came out that year. He compares the four of us – myself, Sonnet L’Abbe, Lorna Goodison, and George Murray – to Charlie’s Angels. He calls Goodison’s work, “take-out exoticism,” L’Abbe’s work has a “tendency to woodenness,” and mine is unintelligible, and insignificant. George Murray’s work is said to sometimes get bogged down, but he has “the poet’s instincts, the knack for turning a good phrase and the verbal grit and suppleness to keep the reader engaged.” The illustration accompanying the review is of Drew Barrymore, Bill Murray, Lucy Liu, and Cameron Diaz from the 2000 film Charlie’s Angels. So outrageous, not to mention racist and sexist, as to be almost comical, but guess what? Not. And what recourse did we have? George Murray wrote a letter to the editor expressing his disgust, if I recall correctly, which was not published. And that was that.

Except for the fantastically clever review I got in the Calgary Herald by Sid Marty. He describes a metaphor he’s not impressed with as a “fragment of lasagna.” Again, I guess he’s trying for comedy? After several paragraphs expressing his deep distaste for my poems about Venice, he concludes, “Those who knows this world may applaud Shawna Lemay as an imaginative genius, a cosmopolite far beyond the grasp of rustic Canadian poemslingers. In fact, if this deeply flawed work doesn’t win a major Canadian literary award, I’d be pleasantly surprised.” Spoiler alert, I’m sure he was happy that year as the book won exactly nothing. Nor had I expected it to.

Please trust me when I say I was more rustic than cosmopolitan at this time in my life and continue to be so.

Was getting published after this moment difficult? Maybe it would have been anyway. I wrote a couple more books of poetry and then verged off into something I called poem-essays, before moving onto essays and novels. This was likely the trajectory I was called to, anyway. I stopped writing poetry, not because I wanted to but because it seemed futile to keep making work in this genre in an ecosystem that was inhospitable. I was ready for criticism. Criticism is, or could be, healthy. But this was a time when a lot of reviews felt like personal attacks.

Was I devastated at the time? Somewhat. Honestly, of course I was, because as it turns out, I’m human. Reviews pre-internet were rough at the moment but at least we all knew they’d end up at the bottom of a birdcage ere long. The prevailing advice at the time was to not comment on reviews, whether positive or negative. My feeling is that the entire writing community would read them, but then they disappeared, lingering on only in the writers’ minds. In fact, to find these two I had to do a search on a database via the library. I really could have left well alone but I think it’s worth examining, or at least slotting it into what I would call a life in art well-lived.

I mean, the art life, it’s been a struggle! A delight, but also a struggle. My partner, a visual artist, and I have been worried about money for our entire lives. But this was a choice, too, to live this way, so I’m not asking for pity. We’ve worked hard. And neither of us have ever been applauded as imaginative geniuses, sadly and much to our profound dismay. We’ve been looked over for all sorts of things, but isn’t this the case for 99 percent of those making art and writing?

While I wasn’t pretending while writing those first two books that I was doing anything other than looking at repros and armchair traveling, still, I ended up feeling fraudulent, humiliated. I internalized the lasagna comment, I internalized the insignificant comment, I internalized the misspelling of my name, I internalized the deeply flawed comment. Still, I persisted, in spite of.

I’ve seen a lot of art since these books were published. I love looking at art in my own particular way. I’ve learned that you don’t have to be an art historian, or a painter, or a critic of any sort to enjoy looking at art. You don’t even have to be a cosmopolite. You can actually just be a small and insignificant human from latitude 53 in Canada, from a city no single taxi driver anywhere will have heard of. You can look at art and feel some sort of thrill looking at the way paint is layered and blended on a canvas, and see the gestures of the artist’s hand. You can be entranced by a single detail, or a colour, or a particular subject matter. A painting will speak to you and remind you that you’re alive. Huh! How does that even happen?

This October, 2025, we visited Napoli and looked at several paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi including the second variation of her Judith and Holofernes works. We’d seen the larger version in the Uffizi in Firenze in 2024. I’m still drawn to her work; it’s still exciting to see in person. The colours, the details, the resolute expressions in the models are so present, so defiantly and fiercely and determinedly alive. The scale of the work makes you feel as though you are right there peering into the room, seeing the blood on the bedsheets, feeling the tension in the arms of Judith and her maidservant. The colours are so vibrant, hitting the notes with a gorgeous clarity, and this becomes evident when comparing her work to other works in the same gallery. One can feel how molten anger is transformed into the passion felt in this work.

In an article in The Guardian, Jonathan Jones says that Artemesia Gentileschi “deserves to be one of the most famous artists in the world.” While you might not have heard of her, you likely have heard of Caravaggio who was said to drop by the Gentileschi household to see her father, Orazio, also an artist, when Artemisia was a child. Jones says that in court documents there is the casual mention of “Caravaggio coming round to his house to borrow a pair of angel wings.” (A detail that pops out to me because of my “angel” book). There was the example of male artists sharing props, which also feels symbolic or instructive. Artemisia had a lot to share, too, but it would manifest in her work, in her subject matter, and some of it would have to time travel. (There were decades when her work reportedly gathered dust in museum racks).

When she lived in Napoli, she wrote to a wealthy patron defending the prices she charged, saying, “I will show Your Illustrious Lordship what a woman can do.” A number of the women she depicted wear gold garments. And the colour symbolism in the baroque isn’t a surprise—the colour gold evoked power, wealth, the divine, and sacred radiance. She knew what it meant to spin straw into gold. In the larger Uffizi version, Judith is wearing a gold dress, where in the version in Napoli’s Gallerie D’Italia is wearing a celestial blue. Still, she is known for her use of gold, sometimes called Artemisia gold. Caravaggio’s Judith and Holofernes depiction of the same subject is also harrowing but the maid servant stands by holding a sack for the head, while in Gentileschi’s version, Judith and her maid servant work together to overpower Holofernes. Gentileschi’s painting furthers what Caravaggio did in his – which is a kind of homage. At least I feel it as an homage rather than a case of one-upmanship.

Nemesis culture originated with Roxane Gay who I followed back in Twitter days. She reportedly had about six of them and claimed to wish no more harm to them than the occasional mild papercut (not even a deep one). In 2013, Gay tweeted, “My nemesis is having a good year professionally and has clear skin. It’s a lot to take.” A nemesis can be used for inspiration, and sometimes one might truly admire one’s nemesis. A nemesis might just light you on fire and spur you on to do your life’s work. Who knows? All I know is that I have this one inspiring and delightful and ridiculously talented friend, Adriana Onițǎ, who writes down the names of all her friends’ nemeses in a notebook. Your enemies are her enemies, she says. And I can tell you, the act of someone taking the time to record the names of your enemies with proper flare and accurate spelling is wonderfully cathartic.

I learned also, with a distance of 25 years or so, that there is a lot of comedy in talking about the reviewer who writes about your poems about travellers to Venice, Italy in terms of lasagna, or who designates you as one of Charlie’s actually kick-ass Angels. Comedy gold, really. And it’s all fine, because are you even Canadian if someone hasn’t tried to chop you down like a tall poppy? Are you even an imaginative lasagna loving genius? You’ve likely heard the joke about how being a Canadian artist or writer is like being in the witness protection program. It really is hard to sustain yourself here if you fit into the minor writer category which I most decidedly do.

I stopped writing poetry at a certain point, good party though it was. Coulda been the whiskey mighta been the gin, coulda been the humiliation coulda been the freeze-out. I kept moving toward where the love was. Maybe poetry left me, and maybe it’ll come back some day. What has always seemed perverse to me though is that poets could form inhospitable communities. But in the end I’ve found my own small community of hospitable and openhearted writers and that has made all the difference.

The entire time I’m writing this I’m asking myself: Why am I bothering with this now? I don’t think those who wrote these reviews would likely wish to take back their words. Nor do I wish to shame them, though I also believe I own those experiences as Anne Lamott would say. In fact, I would extend some grace if I thought it would be welcome. I know I was handed books to review years ago that I would approach differently now. There are books that I ought to have handed back to the reviews editor but because I needed the money, I forged ahead. So we give grace, and if we have wished some mild papercuts here and there upon certain nemeses, perhaps that will be forgiven. If I were to write reviews these days, I would ask myself, how could my words be both honest and truly useful to the writer at hand?

Maybe it’s useful to think about how you get from one place to another alongside a history that’s recorded elsewhere and by others who give you nary a thought. Maybe your little tale, though it’s not one of woe, will spark others to share their tales of just getting through in spite of. Maybe they all add up to something and some day that will hold meaning for one soul or another. A picture might form in the imagination.

To write about our nemeses, our literary and other humiliations, our various artistic passions and hopes and struggles – why? To be of use? So as to connect with others who have or will experience same, to say, you are not alone in this? (You are not alone in this).

I recently wrote here about how an interval of doubt can be useful, clarifying, and it can create in you a permission — you allow yourself to be a beginner, to play, to go places you might not have gone otherwise. And the thing is, is that uncomfortable spot of doubting is rather crucial isn’t it? So here again, I pledge to sit with the doubt for longer. Doubt is the friend. I repeat, doubt is the friend. That said, too much doubt saps the energy, and these days our creative juices, our energies are ever more valuable. In the immortal goddamned words of Taylor Swift, we really do have to ultimately shake it all off.

Did the reception of my first two books inform the rest of my writing trajectory? In some ways, yes. I often think about Hélène Cixous’ words: “Fecundity is the creative person’s natural state.” When we’re not overflowing it’s usually because of outside obstacles. And there is never any shortage of those.

We all know the myths around artists and writers, that you must suffer for your art, starve for it, be the poor starving artist. The rest of the world has become more hostile to art making with the advent of AI, some knowingly, some unknowingly. I imagine our AI overlords will only further manipulate the creative class, pit us against each other in ever stranger ways, as the market for human-made becomes more slim and people become more zombie-like.

In our more secular world, we might not know the story of Judith and Holofernes so well. The city of Behulia nearly falls to the invading army due to Holofernes halting the water supply. Judith enters the camp, seduces Holofernes, gets him drunk, severs his head, and returns to the city with it. Meanwhile, in 2025 massive water sucking data centers are being built with untold (though scientifically predicted) devastating harms on the way. Instead of Holofernes we have the 1%.

The courage of Artemisia Gentileschi to take the humiliations and violent abuse she suffered and turn it into art deserving of the highest accolades still inspires today. She imagined more for herself, and for her daughter.

C.D. Wright wrote that “enemies are energizing but that fuel is short-lasting.” That fuel is poisonous in the long run; that poison is sapping. What is possible is to convert poison into imagination. “Follow the lights in your own skull,” said C.D. The words that come out of your own well-lit skull – this is where the good energy is, the sustainable fuel, the food.

How do we imagine ways to lift each other up at this point in history? How do we imagine communities of creatives who can provide critical direction but within a framework of usefulness?

What do we hunger, thirst for as writers now? It’s all tied up with money, as it always has been. Virginia Woolf reckoned on 500 pounds a year as necessary for the writing life and the life of the mind, and in one of the poems I wrote about Artemisia she speaks about the expense of painting, being underpaid for her work, and having to survive on a thin soup and stale bread. These days writers who often rely on side gig work to support their writing life, such as editing, ghost writing, and freelance writing, are now currently being edged out by AI.

It's not just about surviving the writing life though, with the bare minimum. How can one thrive, delight, flow, be fecund, be sharp and thorough and wild, and incisive and surprising and how can we throw our gorgeous and tender and broken hearts into this enterprise? How do we persist, continue, and how can we be unflinching, rolling with the inevitable punches? How do we overcome the obstacles? for obstacles there will always be... (To echo Woolf’s “For interruptions there will always be.”).

I think most of us stopped imagining that the creative life would ever get easier, but suddenly it seems like it will be getting harder than ever. And it’s still hard for me, 13 or so books in, 35 years or so in. But I worry about the young writers, all of them. The ones who haven’t even begun to imagine a writing life for themselves. The ones who live in a world with drugs that affect your appetite, making you feel hungry when you’re not, and others that make you feel sated when you might need nourishment. And it makes sense to take drugs for depression, anxiety, diabetes. It does. It makes sense to be afraid right now. It makes sense that many are in a recurring flight or fight response mode which elevates cortisol levels and which according to Harvard Health could in a chronic case cause, “brain changes that may contribute to anxiety, depression, and addiction” and weight gain.

One must continue to ask as Woolf did, “Now what food do we feed women as artists upon?” What new considerations are there? As a white woman writer in my 50s in the mid 2020s, of what use can I be? Is it helpful to tell my story? Or is it better just to get out of the way to make space for others to articulate theirs? How do we make meaning of our own ongoing stories at this particular historical moment? How do we balance the needs of our stomachs so that our small eyes can imagine an enormous and nourishing future?

Love this post? Consider becoming a supporter. (Link below).

This is a longer than usual post which I know is not for everyone! No worries. Back to regular programming in my next one. Cheers,

Shawna