Still Life and Consumer Culture

I very often use my blog posts as a sort of notebook to collect thoughts on something I want to think about or write about more in depth. This will certainly be one of those posts, containing some admittedly only very cursory thoughts. Of course, how can any of us really be thinking about anything other than Black Lives Matter and how we can use this time we have to think deeply, which is something Lucas Jonson advises in a conversation with Krista Tippett. He says,

“To go back to the question that you asked, I think that this is a brilliant opportunity for us to think deeply — think profoundly, think without limitation, think with bold imagination — who are we going to be to each other. In such unrestrained ways. In such vulnerable ways. This is an opportunity for us to really reimagine the very structure and nature of our communities and the structure and nature of our lives together.”

What I want to investigate further and think more about is the way that Covid-19 and the pandemic intersects with and reveals systemic racism. In an article published in May, about the history of pandemics, in the context of the 1918 flu, Lizzie Wade says,

“In the United States, that pandemic did nothing to blunt structural racism. “The 1918 pandemic revealed the racial inequalities and fault lines in health care,” Gamble says. At the time, black doctors and nurses hoped it would prompt improvements. “But nothing changed. After the pandemic there were no major public health efforts to address the health care of African Americans.”

Could the COVID-19 pandemic, by revealing similar fault lines in countries around the world, lead to the kinds of lasting societal transformations the 1918 flu did not? “I want to be optimistic,” Bristow says. “It’s up to all of us to decide what happens next.”

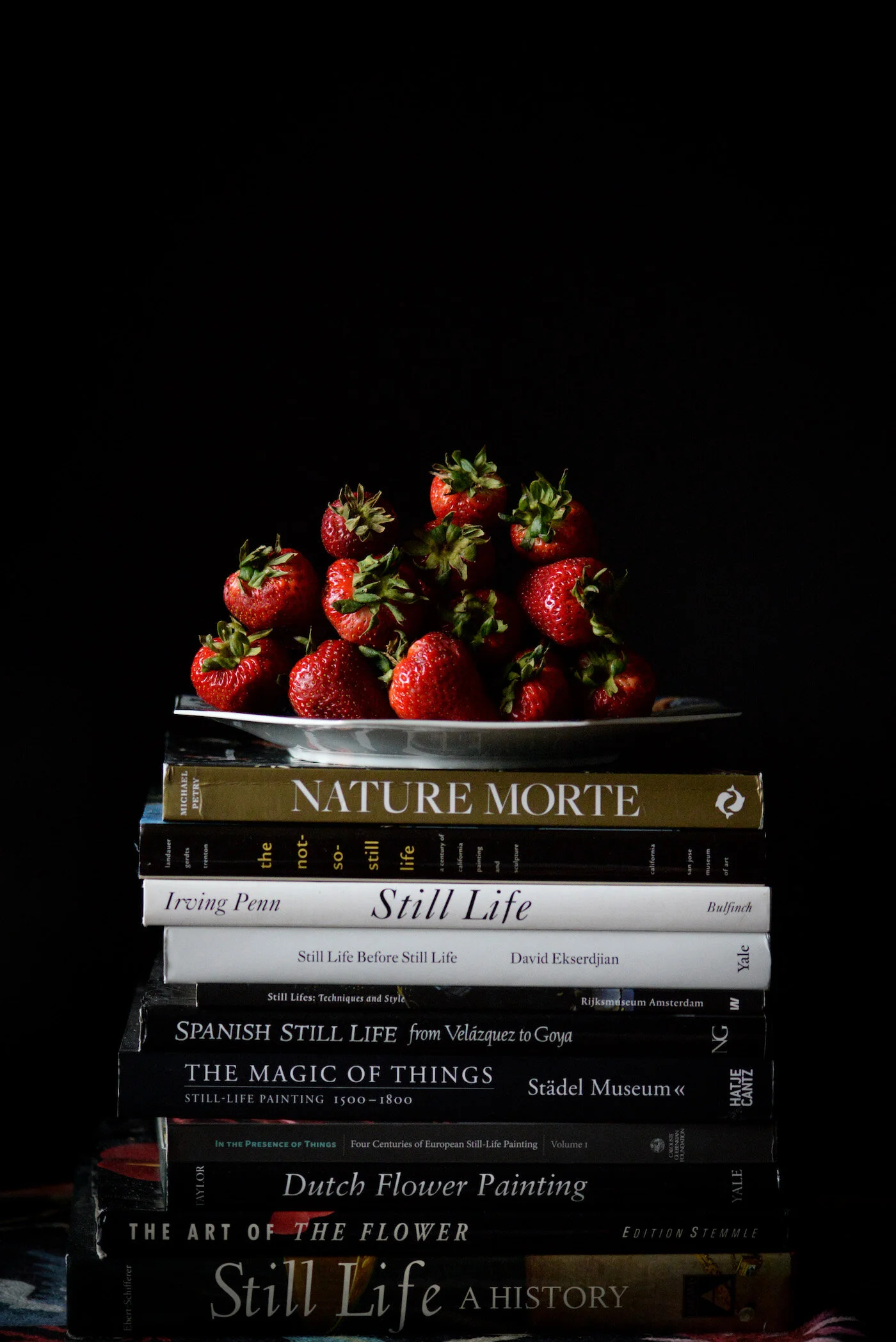

So yes, we are now in the stage where things have gotten real. I keep thinking of the scene in the series, Sanditon (based on the Jane Austen fragment) where the pineapple is found to be rotten to the core, and is quite obviously a symbol of “Britains colonial legacy” and tied to “a history that is intrinsically tied to the theft and exploitation of indigenous land and enslavement of African people.” (from The Daily Beast). Still life is an interesting site to look at inequities because it’s a site of our capitalist consumerist society. It might at first glance seem like quite an innocuous study, a slight one, in light of the real danger that people face every day in our time, and comparatively obviously, it is. But when we start to think about who has access to the food on a table, how the food gets there, who delivers the food, produces the fruit, who can afford to eat what, and who labours in the fields, it starts to get stickier.

In the book, Still Life and Trade, Julie Berger Hochstrasser says in the preface:

“…it is not just the abominations of slavery and colonialism per se but rather the larger workings of capitalism that have brought us to this point where inhuman inequities of many kinds can continue to generate such proportionate profit in the world: distant markets and unseen sweatshops are too much with us still. So in this respect the account that follows will ultimately confront the evidence of the dazzling still life paintings of the Golden Age of Holland as sober lessons. To a postmodern eye, the allure of those rich commodities served up on silver platters without any troubling details regarding their acquisition reverberates shockingly in the glitz of today’s advertising images that can gloss so seductively over just such disturbing realities of production. Can we learn from their unpacking?”

Like in still lifes, we have always known there is a dark and sinister side to the objects and food on our table. In an article on the dark side of Dutch Still Lifes of the 17th century, Julia Fiore remarks on the presence of the sugar bowl: “The sugar obliquely references one of the most barbaric elements of the global Dutch empire: the horrific, widely documented treatment of slaves on South American plantations.” And that’s just one example.

So once we know the metaphorical pineapple is rotten, once it’s cracked open and looked inside, then what? We can’t go back to thinking about it in the same way, and we certainly can’t consume it any longer. We need to stop glossing over the troubling details. We must change how we live our lives, on so many fronts.