What Are You Going Through?

“How much time do you devote each day to thinking?”

– Simone Weil

This is the epigraph to the introduction of a book I have been utterly absorbed by this past week, titled The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas by Robert Zaretsky. I learned of the book in The LRB in a review which Zaretsky responds to in a letter in the footer of the review. I’ve long had an interest in the work of Simone Weil as many of you who have read my book Rumi and the Red Handbag will know. The central question of that book is “What are you going through?” which is taken from Weil’s discussion of the Grail King, and which Zaretsky explores with an anecdote from his life.

The criticism in the review of Zaretsky’s portrayal of Weil as a “Simone of the suburbs” annoys him, and hey, me too — it’s wrong on a couple of levels. But it’s fine because I bought the book because I wanted to find out more after reading the review. So. What I’m always interested in is the nature of work, which always brings me back to either Simone Weil or Bruce Springsteen. And then of course, how the question plays out in my daily life, in my work life at the library where (in normal-ish times) we spend what many would find to be a surprising amount of time helping the houseless (the term homeless is less used these days). While writing Rumi and the Red Handbag I was interested in the philosophy of the soul, in human suffering, and in the difficulty in asking that question, What are you going through? I was inspired by Weil, but also by Clarice Lispector, in particular The Hour of the Star. It seemed to make sense to explore these interests, obsessions, questions, through fiction, through a character — Ingrid-Simone, whose initials she wrote, I.s.

And these days, I can’t help but asking myself, how do we exist? What is existence now? If I’m going through this and this and this, what are you going through?

Of course, a novelist should leave the talking about her work to others, but there’s a start for you. In the review of the Zaretsky book, Toril Moi says:

“At the same time, The Need for Roots is radical and extremely inspiring. It is rightly famous for its first section, setting out the ‘needs of the soul’. Here Weil rejects all ‘rights talk’. We should not focus on rights, she argues, but on obligations. Obligations (devoirs) precede rights; rights are situational and relative, obligations are metaphysical, absolute and eternal. How do I know what my obligations are? An obligation arises from the very fact of encountering another human being. If I encounter a starving human being, I am not in doubt: I offer food.”

And honestly, I think about all of these things when I’m interacting with those who are precarious or vulnerable or at-risk whether mentally or physically or due to a myriad of circumstances — when I’m at work. While I have an MA in English literature, I suppose I’ve always been drawn to a less academic working out of these questions, a way of living with them, working them through alongside. What are the needs of the soul and spirit and what are our obligations to others in helping to fulfill these? What is our obligation to someone who is hungry and thirsty? These are not academic questions at the library. We encounter hungry people all the time. Literally thirsty people. And yes, there is no doubt.

What’s been (sort of) interesting about working through the pandemic is how difficult it’s been to think. I only work half time and yet, my ability to really delve deeply into a book or subject has been wanting. The library went through cycles of being closed and open but was always doing curbside pick-ups and this was quite honestly more like factory work. In the Zaretsky book he says,

“The act of thinking, Weil discovered, was the first casualty of factory work. A few days into her job, she was already reeling from fatigue. At times, the unremitting pace reduced Weil to tears. In one unexceptional entry, she wrote: “Very violent headache, finished the work while weeping almost uninterruptedly. (When I got home, interminable fit of sobbing).”

In her factory work, Weil said that she profoundly felt “the humiliation of this void imposed on my thought.” What are the rights of workers now, and what are our obligations to them?

Which is not to say that my own work felt humiliating, not at all, but that it was different, and repetitive and physical, and exhausting in all new ways. And then, add in the layer of the pandemic, that low-level stress we’ve all felt in one way or another. Maybe one day, years after this time, we’ll sit down and think and talk about that, too. The bone-tiredness, the unrelentingness of it, all of the ways that class and hierarchies came into play. Who gets to be relatively safe and who doesn’t? Who is “essential” and who is not? Will we ever think of work in the same way again? Will we be more grateful for grocery store workers, for example?

You see, I’m tired, writing this even, where before the pandemic I could have just riffed away and not worried too much about what I’d end up with. Have I even talked about the book I came here to talk about? ha. Well. I think the reason why I liked it so much, though, was that it spoke perfectly about our time without being overt about it. And it didn’t try to console. Zaretsky says of Weil:

“As with her life, so too with her ideas: they perplex and provoke, dazzle and inspire. More rarely they console, but perhaps consolation is not all that it is cracked up to be. More important, perhaps, is comprehension. “Only the greatest art,” Murdoch noted, “invigorates without consoling.”

And I suppose this is why I’ve always been drawn to Weil, and why this book held my attention when so many others have not this past pandemic year. (You should see all the dog-ears and underlining). I don’t want consoling, I want deeper thinking, and I want to consider our obligations.

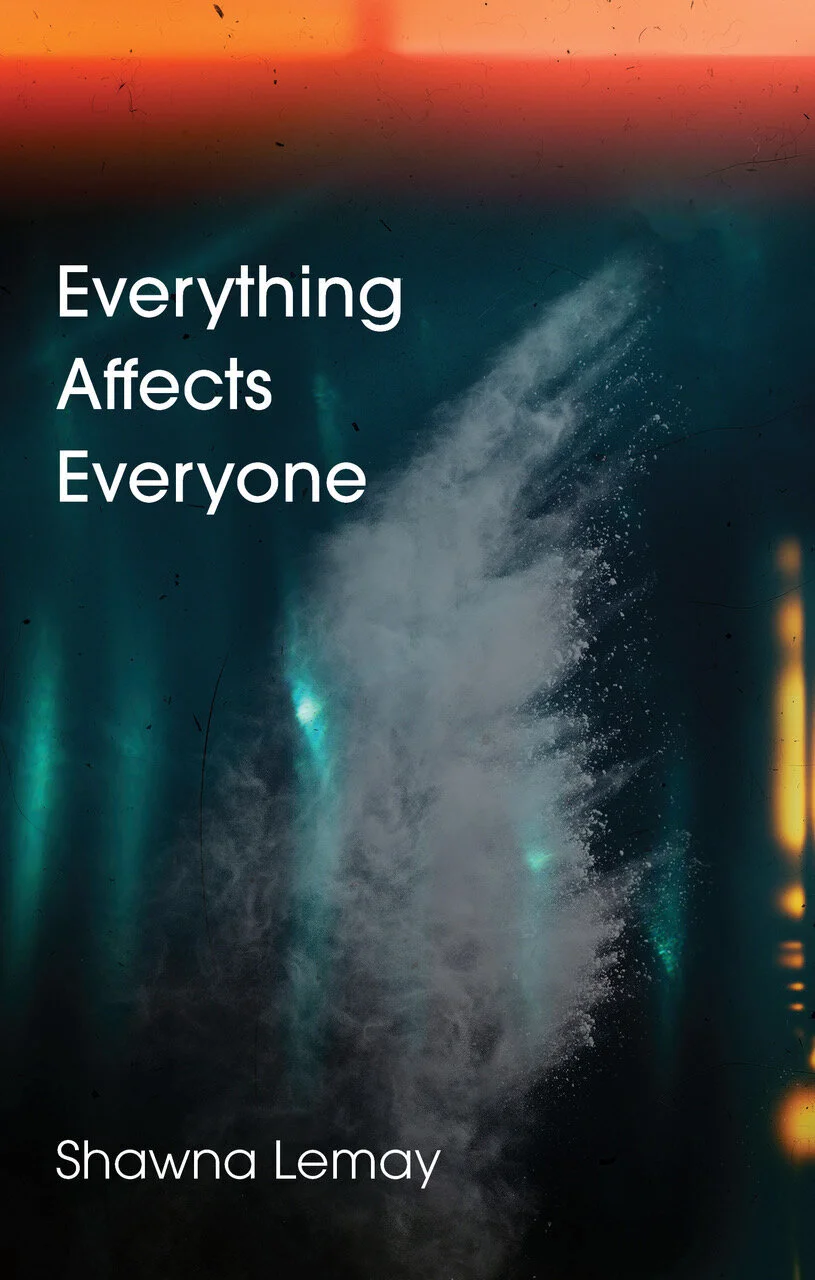

Which brings me to the news that my novel, Everything Affects Everyone, is now available for pre-sale through my publisher and through many of your local bookstores. For example, in the US it’s listed for pre-sale at Barnes & Noble. Obviously, any of the Indies will pre-order it for you, too. As you probably know, pre-sales make a huge difference for the author, and really kickstart sales etc. Everything Affects Everyone will be out mid-October and so thanks in advance for following along with me in the adventure of the introverted author trying to sell her wares :)

While the central question of Rumi and the Red Handbag is “What are you going through?” the central through line in Everything Affects Everyone is from Clarice Lispector:

“All human beings experience annunciation. With pregnant souls we raise our hands to our throats with surprise and anguish. As if each of us had learned at a given moment in life that we have a mission to fulfill.

That mission is by no means easy: each of us is responsible for the entire world.”

The novel has as its subject, angels, photography, seeing, belief, movie stars, women in conversation, and art theft. (Thank you for listening to my sale pitch, haha!). While it wasn’t written during the pandemic, one thing we have learned is that truly, everything affects everyone.

July 8 2021